Zackery’s Story

It was 2006, and as the first half of a junior high school football game was coming to a close, 13-year-old Zackery Lystedt tackled an opponent and hit the ground head first. Lying face down, he clutched the sides of his helmet in agony, but did not lose consciousness.

Zackery sat out three plays and returned in the third quarter. At the end of the game Zack, a gifted athlete who played both offense and defense, collapsed on the field.

He was airlifted to a hospital for emergency brain surgery and 3 years later after falling into a coma, suffering strokes, being on a ventilator and a feeding tube and unable to talk, he was finally able to stand on his own two feet with assistance (CDC, 2013).

In 2009, three years after his devastating concussion, the state of Washington passed the “Lystedt Law” assuring that young athletes are examined and cleared by a health care professional before returning to play.

The enduring impact of Zackery’s story has resulted in this law being implemented, with slight variations, in every state in the union (Kreck, 2014).

How Prevalent Are Concussions in Youth Athletics?

In the United States, between 1.1 and 1.9 million concussions in sports and recreational activities occur each year in children 18-years-old and younger (Bryan, et al 2016). This number includes estimates of undiagnosed or untreated concussions as well.

Estimates of untreated concussions in high school range from 22.5% to 52.7%, and in one alarming study from 2014 it was found that 55.9% of female middle school soccer players with symptoms of concussion were never evaluated (Bryan, et al 2016)!

The Centers for Disease Control & Prevention provide some important insights to better understand the dynamics of how and why concussions occur in youth sports. Many young athletes hide concussion symptoms, with 7 in 10 admitting that they have played with concussion symptoms, especially in a big game. More alarming than that, 6 out of 10 of those said that their coach was aware of it. 25% of the reported concussions in high school are the result of aggressive or illegal play. 70% of concussions in young athletes are due to player-to-player contact with the rest being contact with the ground or an obstacle (CDC – Brain Injury Safety tips and Prevention).

Despite the new laws inspired by Zackery’s story and the awareness in our communities, schools and the media, concussion rates in young athletes is on the rise (Tsushima, et. al 2018).

Some of the reasons for this disturbing trend can simply be explained by the increase in concussion education and the recognition of symptoms and management policies, as well as increased participation in sports and recreation. However, a portion of the rise in concussion risk may be from athletes that are bigger, faster, and stronger creating bigger magnitudes of head collisions (Tsushima, et. al 2018).

The Impact of Age

In a study by Tshushima, et al. (2018), of over 10,000 middle & high school students from 67 schools during one year of athletics, it was found that the overall incidence of concussion was 12.1%. The relative risk was almost twice as high for 18-year-old athletes in comparison to 13-year-olds – most probably as a result of being bigger, stronger, more competitive and having more playing time.

Is There a Gender Difference in Concussion Risk?

Girls had a 1.5 to 2 times higher risk of concussion than boys in comparable sports. There are many proposed reasons for this disparity. The most obvious is that boys would tend to minimize injuries more often and underreport symptoms to continue to play. It has been shown as well that girls exhibit more neuropsychological decline post-concussion than boys.

Girls had a 1.5 to 2 times higher risk of concussion than boys in comparable sports. There are many proposed reasons for this disparity. The most obvious is that boys would tend to minimize injuries more often and underreport symptoms to continue to play. It has been shown as well that girls exhibit more neuropsychological decline post-concussion than boys.

Other proposed mechanisms for this disparity were differences in body mass, neck strength and ball-to-head ratio, as well as neuroanatomical and hormonal factors. Pfister et al (2016) also propose that females exhibit greater angular acceleration of the head and neck.

The Effect of Prior Concussions on Future Concussion Risk

A surprising fact is that young athletes who had a prior concussion, had a 3 to 5 times greater chance of getting a concussion than those with no history of concussions! One reason for this could be the high school athletes getting concussions are the more experienced players and are getting more playing time. There is also evidence that besides the short-term effects of a concussion, long-term impact could affect neuronal plasticity and compromise the capacity of the brain to sustain repeated traumas, increasing the risk of another concussion.

Which Sports Pose the Greatest Risk of Concussion?

Youth sports that have been shown to have the highest incidence of concussion are rugby, with the highest rate, followed by hockey, and American football (Pfister, et al. 2016). Additionally, high concussion rates have been documented in wresting, martial arts, and cheerleading (Tsushima, et al. 2018), as well as boys’ lacrosse and girls’ soccer (MedStar Sports Medicine, 2008).

Youth sports that have been shown to have the highest incidence of concussion are rugby, with the highest rate, followed by hockey, and American football (Pfister, et al. 2016). Additionally, high concussion rates have been documented in wresting, martial arts, and cheerleading (Tsushima, et al. 2018), as well as boys’ lacrosse and girls’ soccer (MedStar Sports Medicine, 2008).

Well, that’s a lot of scary info on concussions, but what exactly is a concussion and what are the long-term effects?!

Definition

The Micheli Center for Sports Injury Prevention describes a concussion as “…a brain injury that occurs when a blow to the head causes the brain to spin in the opposite direction from where the head was struck – what doctor’s describe as a ‘rapid, rotational acceleration of the brain.’”

A concussion results from either a direct blow to the head, or violent shaking of the head or upper body. With a violent blow, the brain slides back and forth hitting the inside of the skull. This damages nerves that then can release toxins causing damage to other nerves.

Symptoms

Signs of a concussion may include headaches, vision problems, ringing in the ears, dizziness, nausea, confusion, vomiting and amnesia (Mayo Clinic). It is important to point out that many of these signs will not be immediately apparent and those who suffer a concussion do not always lose consciousness. So, it is possible to suffer a concussion and not even realize it!

Complications

Some long-term complications include post-concussion syndrome where the symptoms described above persist days, weeks, or even months after a concussion. Especially if proper post-concussion care is not implemented.

The cumulative effect of multiple concussions over a lifetime has been shown to increase the risk of developing progressive and lasting brain function impairments.

Finally, second impact syndrome occurs when an athlete experiences a second concussion before the symptoms of the first concussion have fully resolved. This can result in rapid and possibly fatal brain swelling.

Differing Effects on Kids, Teens, and Adults

Young athletes may be at increased risk for concussion due to larger head-to-body size ratios, weaker neck muscles, and/or the increased vulnerability of the developing brain.

Pfister et al. (2016) note evidence that shows that children and teens have longer recovery times than adults after suffering a concussion and that they require a more stringent approach to injury care and return to play.

In the Education Commission of the States on Student Safety regarding concussions (2014), a study was highlighted pointing out that teens were even more fragile than children or adults after a concussion, and that the effects could last 6 months or longer! A possible explanation for this is that their frontal lobes are growing in spurts, making them more susceptible to injury (Krek, 2014).

Sub-Concussion Risk

With all the talk about the devastating effects of concussions, there is an even greater risk of ignoring the impact of repeated non-concussive hits, known as subconcussions. These hits can be direct or just to the body causing a shaking or sudden acceleration of the head.

Because there are no immediate signs or symptoms of a concussion, athletes will continue to play and risk even more chances to accumulate damage that results in potential long-term impacts as the brain experiences unresolved inflammation and never properly heals. Studies have shown subtle deficits in working memory and neurological changes in parts of the brain (Hickman, 2019), as well as a possible link to the development of CTE, or chronic traumatic encephalopathy (Crawford, 2018), which leads to damage or death to parts of the brain over time resulting in memory, judgment, and mood disorders, and even dementia.

Ok. Now What Can We Do About It?!

As a parent and a coach, my first question after realizing how scary all this is, is how can we best prevent a concussion?

The first step was started by Zackery Lystedt’s compelling story with sweeping laws that push 3 mandates (Kreck, 2014):

1. Education requirements for athletes, coaches, and parents

2. Removal of a player suspected of having a concussion

3. Return to play only after at least 24 hours on approval of a health professional

Since the introduction of these laws more kids self-report symptoms and pull themselves out of the game. But the ultimate proof of the effectiveness of these laws are that repeat injuries fell dramatically from 14% of all concussions in 2005 to about 7% in 2016. (Yang & Podell, 2017).

While this is a great first step, you will notice that none of these laws address changes that can prevent an initial concussion.

To prevent concussions, as well as the cumulative effect of subconcussive impacts, here are some of the proposed rule changes, coaching tips, equipment recommendations, and training protocols that may prove beneficial:

- The Concussion Legacy Foundation (CLF) has proposed flag football for kids younger than 14 (Crawford, 2018). This could greatly reduce the effects of subconcussive impacts as well as decrease or eliminate the total amount of concussions a young athlete endures. Proponents point out that NFL greats such as Jerry Rice and Tom Brady did not play tackle football until after age 14. Opponents say that by not training in proper tackling techniques early, young athletes put themselves at greater risk once they begin playing against bigger and stronger players after the age of 14.

- The Arizona Interscholastic Association restricts coaches form holding more than half of pre-season practices in full pads.

- In Texas they limit the amount of full contact allowed in practice to 90 minutes per week.

Texas also prohibits using helmets that are 16 years old or older (Kreck, 2014):

Texas also prohibits using helmets that are 16 years old or older (Kreck, 2014): - While making sure equipment is of high quality and properly fitted, no level of equipment quality can fully prevent a concussion. Helmets can help, but research regarding mouthguards has shown that they are ineffective in reducing the severity of a concussion (Pfister et, al. 2016).

- Teach proper technique in contact sports:

- Girls tend to have a higher concussion rates in soccer. One possible reason seen in studies is that girls tend to close their eyes more often while heading the ball than male players do (Honda et, al. 2018).

- Two successful ways to teach tackling in American football to reduce concussion risk are (Athlete Intelligence, 2018):

- “Heads-Up Football” where players are taught to make contact by rising into the ball carrier with their chest and shoulders, keeping their heads back.

- “Rugby-Style Tackling” where the tackler keeps his head to the side while driving the shoulder into the thigh or chest of the opponent.

- Train young athletes with a well-rounded strength, conditioning, movement, and sensory awareness protocol:

- Certain skills are best developed by kids from 6 to 12 years old. Focus on honing agility, eye-hand coordination, and general conditioning (Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, 2019).

Although some studies have mixed results, there is evidence that visual awareness training, to include peripheral vision training, as well as reaction time training, and neck muscular strength training all have reduced the incidence of concussions in young athletes

- Visual training consistently showed results of reduced concussion in collegiate football. Being able to effectively use peripheral vision as well as quickly locate and track a ball or opponent allows them to react faster and avoid collisions or brace before a collision (Honda J, et al. 2018).

- Studies of neck muscle strengthening has also had mixed results, but many studies do show that athletes with stronger neck muscles are able to withstand the impact of head contact and diffuse it through the muscles (Honda J, et al. 2018). One study showed that starting neck strength and girth in many high school athletes in various sports predicted concussion rates with a decrease of 5% for every one pound strength increase in neck muscles.

- Reaction time training has been the only intervention that all the studies agree can help prevent concussions. Studies show fewer hits on the head as well as less magnitude of any hits sustained (Honda J, et al. 2018). With faster reaction times, athletes are able to anticipate hits and protect their heads from impending impact.

- Baseline measurements of cognitive and physical performance are useful for detecting if a young athlete has sustained a concussion by simply re-testing and comparing results.

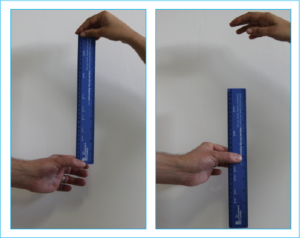

The ruler-drop test is where a ruler is dropped from a pre-determined height and the place on the ruler where the athlete catches it is recorded. Honda j. et al (2018) suggests that not only is this a great way to test reaction time and susceptibility to a concussion but it is a cheap, reliable and valid test to use as a baseline post-concussion comparison test.

Post-Concussion Care: Proper Rest

Once a young athlete has sustained a concussion a full recovery is possible if the proper protocol is followed. Typically, concussions should be fully resolved within 3 weeks. Moser and Schatz (2012) showed that even many months after a concussion if proper protocols are implemented a full recovery can be achieved.

The catch… it ain’t easy! It requires cognitive and physical rest such as time off from school, no homework, no reading, computers, video games, texting, use of cell phones, or TV, no exercise, athletics, or chores that cause exertion or sweating, no trips, no social visits in or out of the house, and finally increased rest and sleep. The last one should be easy as there is clearly nothing else left to do!

Conclusion

As you can see, we’ve come a long way in a short time in our understanding of what a concussion is, what the signs and symptoms are, and what the short and long-term implications are. The laws enacted since Zackery Lystedt’s tragic concussion are a major first step in awareness and protecting youths once a concussion has occurred.

But the most exciting research has been in how, as parents and coaches, we can protect our kids with an improved understanding of the signs of a concussion, as well as how to effectively target our training to reduce the risk.

General conditioning, sports technique, and Strength training, especially of the neck, traps, and upper shoulders should be the base of any well-structured program. But by including sensory awareness training with visual awareness drills, agility, and reaction drills, it could mean the difference between an enduring lifetime of competitive sports and recreation or serious and even life-threatening consequences down the road.

For a reference list and some basic prevention activities for young athletes, contact brett@spiderfitkids.com.

Craig Valency, MA, CSCS, president and co-founder of SPIDERfit, has been a personal trainer for the last 11 years. He is currently working at Fitness Quest 10 in San Diego, an elite personal training and athletic conditioning facility. He specializes in youth strength and conditioning programs that promote physical literacy, injury prevention and optimal performance. Along with training youths from 6 to 18 years of age for general fitness, Craig has also worked with some of the top junior tennis players in the world. He has been a physical education consultant for the Stevens Point school district in Wisconsin for the last 3 years, helping revamp the district wide programming for the K-12 PE curriculum. Craig earned his bachelor degree from UCLA, and Masters Degree in Kinesiology from San Diego State University.

Texas also prohibits using helmets that are 16 years old or older (Kreck, 2014):

Texas also prohibits using helmets that are 16 years old or older (Kreck, 2014):

Connect with SPIDERfit!