If you work with kids in any capacity, it’s goes without saying that their thoughts, motivations, and actions are very different than those of an adult.

In the realm of sports and physical training however, many overlook or are unaware of just how significant these differences are. Parents and coaches often become frustrated when young children lack the attention span, skill acquisition rate, and positive training adaptations associated with their more matured counterparts.

In addition to the frustration felt on both sides, when children are expected to perform tasks outside of their developmental wheelhouse, the risk of injury increases dramatically.

As a fitness and athletic performance mentor for young children, it’s important to understand the factors that make children different from adults so participation, performance, and safety can be the centerpiece of the program.

Consider 4 key differences between children and adults below.

Where do kids get their energy?

From a metabolic standpoint, children derive most of their energy from their aerobic “endurance” system. This is true even when they’re doing high intensity activities where an adult would rely their anaerobic power system to create energy.

Since fat metabolism is  usually associated with the aerobic system, children have a higher ratio of enzymes that metabolize fat than adults do. Kids have up to 60% less glycogen stores in their muscles than adults and have a higher proportion of “intramuscular triglycerides” (fat stored in the muscle).

usually associated with the aerobic system, children have a higher ratio of enzymes that metabolize fat than adults do. Kids have up to 60% less glycogen stores in their muscles than adults and have a higher proportion of “intramuscular triglycerides” (fat stored in the muscle).

This decreased dependence on glycogen means their primary fuel (fat) doesn’t burn as hot, so they don’t accumulate as much lactic acid as an adult does during exercise. Therefore, kids generally don’t need as much recovery between exercise bouts. It’s important to note that children can’t regenerate energy as fast as adults, so they fatigue quickly during high intensity exercise.

What does this mean for coaches?

When doing activities with children, keep the duration of an activity short but realize they don’t need much rest time between bouts. Since high intensity activities don’t necessarily improve the anaerobic power system in children, gains in speed, power, strength, etc. come from learning to do it right (improved neuromuscular coordination). Create a practice environment where the focus is performing activities correctly vs. constant fatigue and overload.

Why are young children so uncoordinated?

When children are born, they are armed with an arsenal of reflexive movement patterns that help keep them alive during infancy. With time and an enriching environment, they learn to override these reflexive patterns and manually program how they want to move. These early unpracticed manual movements have little to no neuromuscular infrastructure to support them. The messages between the brain and body are traveling on dirt roads.

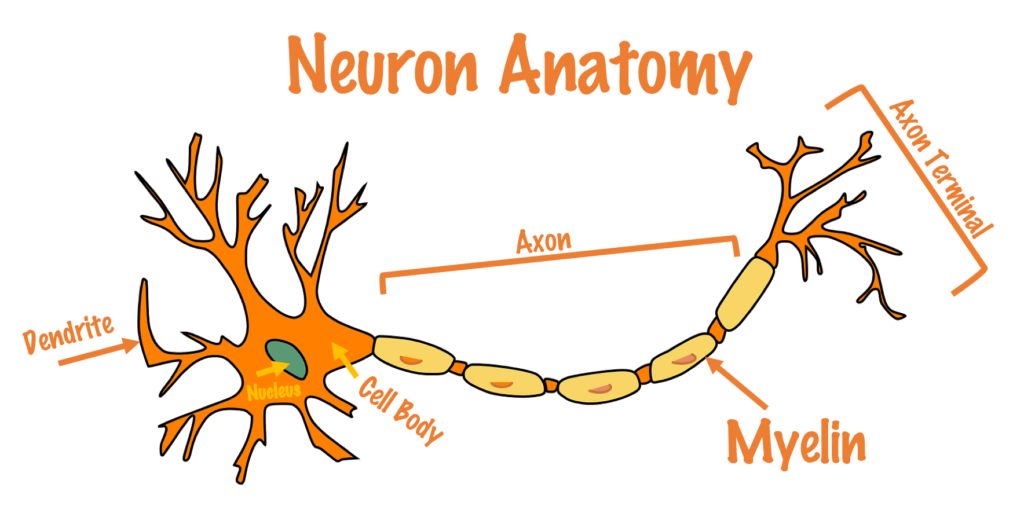

The more a movement is practiced in response to sensory information, the more the neuromuscular roads are used. Soon, these dirt roads become paved freeways. As a product of natural development, by roughly age 7-8, these neuromuscular freeways turn into high speed trains through a process called myelination. Myelin is a protective coating around nerves that insulates them, making neural messages travel faster and more efficiently.

The more a movement is practiced in response to sensory information, the more the neuromuscular roads are used. Soon, these dirt roads become paved freeways. As a product of natural development, by roughly age 7-8, these neuromuscular freeways turn into high speed trains through a process called myelination. Myelin is a protective coating around nerves that insulates them, making neural messages travel faster and more efficiently.

Prior to myelination, movement patterns can be done with a degree of effectiveness but will often lack smoothness and precision. It’s also important to understand that it’s extremely important for kids to have experience with all kinds of different movement prior to this process. In order for neuromuscular dirt roads to turn into paved freeways then eventually high-speed trains, they must be frequently traveled.

What does this mean for coaches?

Prior to myelination, children’s movements will be a bit shaky. Allowing the time and patience to let kids practice new movements allows for the right neuromuscular roads to be built. Don’t expect perfection early on. Additionally, expose children to many different movement and coordination demands at a young age so their entire neuromuscular system is stimulated to grow. Involve them in multiple sports and activities!

How do kids adapt to the heat?

By the age of 3, children have roughly the same number of sweat glands as an adult. The good news is that this creates more sweat glands per square inch. The bad news is that these  glands only produce about 40% of what adults’ do. Additionally, children have a lot of skin compared to their actual body mass. This increased ratio of surface area to body mass makes absorbing heat relatively easy (imagine the skin like solar panels), but when combined with a decreased ability to sweat, dissipating heat becomes more challenging.

glands only produce about 40% of what adults’ do. Additionally, children have a lot of skin compared to their actual body mass. This increased ratio of surface area to body mass makes absorbing heat relatively easy (imagine the skin like solar panels), but when combined with a decreased ability to sweat, dissipating heat becomes more challenging.

When a child’s core temperature begins to rise, they are slower to begin sweating than an adult. Considering that the oxygen cost of walking or running is about 20% higher in children when compared to adults, their risk of overheating in hot temperatures is relatively high. While they can slowly adapt to being in higher temperatures, they do not adapt as quickly as adults.

What does this mean for coaches?

When training children, it’s important to understand they won’t show the usual signs of overheating as quickly as adults will. Be aware of the temperature and conditions and stay out of direct heat whenever possible. Wearing light colors and breathable materials can decrease some heat absorption. Keeping kids hydrated is essential, so allow for frequent water breaks when the temperatures are high.

Take into account that if you are exercising alongside children in the heat, the metabolic impact of the exercise is much higher for them. If something is challenging for you, it is extremely challenging for them, even if they don’t show the expected signs of fatigue.

Can kids see well?

Both adults and children depend largely on vision for sensory feedback. The eye is an extremely complex bundle of nerves, muscles, and unique structures. This infrastructure takes many years to complete.

The macula of the retina isn’t fully formed until about age 6. This structure helps improve close-up focus. Prior to this, kids are functionally far-sighted. The eyeball completes its round shape by about age 9, so tracking objects smoothly becomes easier. Prior to puberty, the nerves that go from the eyes to the brain aren’t fully formed. This can create challenges when judging distance and direction of objects.

The macula of the retina isn’t fully formed until about age 6. This structure helps improve close-up focus. Prior to this, kids are functionally far-sighted. The eyeball completes its round shape by about age 9, so tracking objects smoothly becomes easier. Prior to puberty, the nerves that go from the eyes to the brain aren’t fully formed. This can create challenges when judging distance and direction of objects.

What does this mean for coaches?

Activities that require hand/eye coordination can become extremely frustrating for coaches and children alike. Understanding the limitations of the eyes during development can merit modifications to activities that allow greater opportunities for learning and success.

For example:

+ Use larger objects (i.e. beach balls, etc.)

+ Use slower moving objects (balloons, scarves)

+ Focus on developing proper eye movement, focus, and tracking prior to adding the demands of catching

When a coach understands these and other developmental phenomenon unique to children, it creates an opportunity to adapt training or practice to make it safe, fun, and effective for everyone.

Brett Klika CEO and co-founder of SPIDERfit is an international award- winning certified strength and conditioning coach, author, and motivational speaker with over 20 years experience motivating and inspiring youngsters to a life of health, fitness, and performance.

Brett consults with schools, athletic organizations, fitness professionals, and fortune 500 companies around the world.

Connect with SPIDERfit!